Big Data and Black Twitter

This post is a story of how combining century old linguistic methods with new sources of data can reveal unexpected insights. It's a small preview of my upcoming talk at the annual meeting of the American Dialect Society, where I will discuss my recent research using social media to map previously undescribed dialect regions in African American Vernacular English (AAVE). It's the intersection of historical linguistics, dialect geography, spatial statistics, and #swag.

Prelude: Maps are Cool

I recently took a class with Bill Labov on Dialect Geography: an under-appreciated subfield of linguistics that had a bit of a heyday in the late 1800s, and which is now starting to make a come back, thanks in no small part to popular dialect surveys like this one from the New York Times.

In the class, we learned methods of mapping and interpreting spatial data to glean information about regional variation in language use, and to begin to understand language variation and change. We learned how maps like this were made:

l'Atlas linguistique de la France published from 1902 to 1920 by J. Gilliéron and E. Edmont – added colors from the version in Lectures de l'Atlas linguistique de la France de Gilliéron et Edmont. Du temps dans l'espace, published in G. Brun-Trigaud, Y. Le Berre & J. Le Dû (2005)

...but we also learned how to map data using newer, more sophisticated computational methods. For instance, reading geographic data from a comma separated file and mapping the data in the R programming language. More importantly, we learned what the interaction between geographic features, historical migrations, and a 'snapshot' of linguistic data can tell us about our language and ourselves.

Now, in the late 1800s, there were basically two ways that you could collect data for linguistic atlases: informally known as the German Method, and the French Method. The German Method was the method Georg Wenker used in 1876, when he sent out 50,000 surveys to German schoolmasters who dutifully sent back 45,000 completed surveys. The flaw in this method is that there is no guarantee of standardization as far as how the data is collected and interpreted. The French Method is what Jules Gilliéron used a decade later: send one trained linguist galavanting around the countryside on a bicycle for four years, eating baguettes, drinking wine, and conducting sociolinguistic interviews with everyone he can as he moves from town to town. My kind of job! Both methods resulted in gorgeous, detailed, and informative atlases...decades after the data were collected. More recently, enterprising linguists (among them, Dr. Labov) conducted telephone surveys, resulting in the "gold standard" Atlas of North American English. The ANAE gives an enormous amount of granularity to the study of regional dialects in North America -- seriously, click the link and play around, it's awesome.

Big Data

What the ANAE achieves, it does with a mere 792 speakers, intelligently sampled by region. It is a feat of ingenuity and economy.

However, we now have some intriguing new tools at our disposal, thanks to the internet and social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. To give you an idea: a search for the word "the," -- a pretty good proxy for English use -- returns 607 million tokens in the last month alone. All of it is literally published work. It is, in effect, an enormous corpus of written language. Given the right tools and know-how, anyone can search that published material.

The Speech Problem: Graffiti and The Writing on the (Facebook) Wall

The only hitch is this: writing is not speech. In fact, if you try to figure out how English speakers anywhere pronounce English based on the spelling conventions of academic written English, you're gonna have a bad time. A few sound shifts here, a few hundred years of weird convention there, and you've got a system that doesn't tell you much of anything useful.

Notice, though, I said the spelling conventions of academic English. Many people have a pet peeve they're more than willing to share (especially on reddit, it seems): they hate when others write should of in lieu of should have. This kind of mistake is any historical linguist's favorite thing ever. Why? Because it tells us something about pronunciation. People who write should of have reduced should have to should've and it is coming out in their writing -- should of and should've are totally indistinguishable in casual speech.

It's precisely this kind of error, along with the writings of hand-wringing pedants lamenting the decline of language (among other things), that allow us to reconstruct the pronunciation of Latin as it changed through time. (aside: ever wonder why it's "inconvenient" but not "inpolite"? A historical linguist can tell you why, and when it happened). In fact, we get an enormous amount of phonologically relevant information from things like graffiti dick jokes in places like Pompeii Who says historical linguistics isn't fun?

Error isn't the whole picture though. It's one thing to say that people who struggle spelling will fall back on sounding things out. It's quite another when the non-standard spelling is intentional. For instance, one task for computational linguists interested in Natural Language Processing (NLP) is to group various spellings into sets that computers can recognize are all the same word. To simplify: a computer needs to know that color and colour are the same thing if it's going to process language quickly and effectively. Recent research in NLP has demonstrated that people on social medial platforms intentionally write how they speak. That is, they go out of their way to spell things in a non-standard way in order to better communicate how they talk informally. The best part is that this research holds across languages. While an American might be sittin (instead of sitting), a Dutch user of Twitter may well sitte (instead of zitten). This is especially true the further a dialect diverges from the written standard, as in modern dialects of Arabic. It's also true in AAVE, where the orthography you learn in school can't capture the phonological and grammatical nuances of the dialect -- something that writers like Zora Neal Hurston, Toni Morrison, and Ralph Ellison grappled with.

Black Twitter: Stigmatized Speech, Innovative Writing

Around the time I was taking the class on dialect geography, I stumbled upon a Youtube video purporting to explain #Blackfolkslang. It's a fun example of what linguists call enregisterment: when a dialect feature gets (consciously) noticed and becomes an overt marker of linguistic belonging. A classic example is the stereotypical Brooklynese fugeddaboudit.

Being a native speaker of AAVE (due to childhood speech community), the forms made intuitive sense to me and were a lot of fun. When I showed them to non-speakers of the dialect out of context, however, they were baffled. "What is ioneem? Is that Arabic?"

I thought it would be fun to dig into their use, and see where these forms were used, and how often. I got help writing a script in Python, using the Twitter API and the Twython package to extract tweets, and started using the mapping tools I was learning in R to check them out.

It became an obsession.

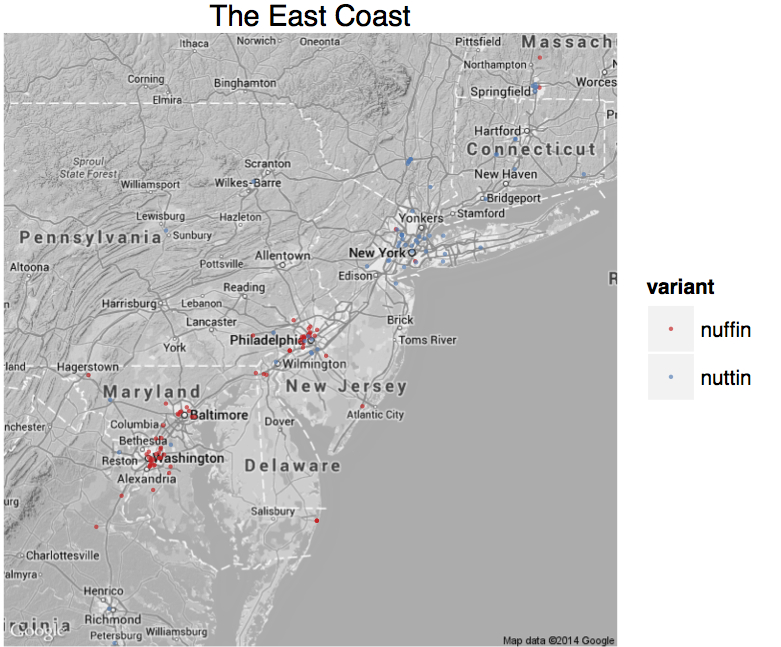

A few months and a few hundred thousands tweets later, I came to a few realizations. First, there's not consensus. Some people tweet nun (for "nothing"), while others tweet nuttin, and others still tweet nuffin. Second, the forms used vary regionally. Third, the phonological clues these tweets provide can be corroborated by both other media and linguistic informants (informant: a fancy term for people who both speak whatever a linguist is interested in and are willing to talk to one). Lastly, there's not just one "Black Twitter." The Black Twitter that blogs, contributes to NPR, and live-tweets sociology conferences was not the Black Twitter I was reading. I was reading tweets from young adults not represented in the Pew Research Center Internet Project, from young gang members who signal affiliation with spelling (fun fact: crips superstitiously avoid the combo "ck" because it could stand for "crip killa," and will instead favor spellings like "fucc"), and from people who use Twitter as a free analog to both texting plans and dating sites.

Some of the writing was not immediately recognizable. For instance, I was perplexed by yeen for "you ain't" (in part because it's not used in NYC or Philadelphia, I would later find). That is, I was perplexed right until I searched for it on YouTube, and came across dozens of different songs, often self-produced, which use yeen in the lyrics. Similarly, nun could conceivably be pronounced in a number of different ways. French Montana to the rescue! People often tweet lyrics to their favorite songs, and quite a number of them tweeted "nigga i ain't worried bout nun". Whether there is a glottal stop or it's elided for some of these tweeters is not clear, but what is clear is that it is two syllables, not one -- the only way to fit the rhythm.

Ultimately, I gathered data on ~30 terms (among them: yeen, talmbout, eem, ion, sumn -- you ain't, talking about, even, I don't, and something, respectively), and found that all of the variation could be explained by recourse to a handful of variations in pronunciation -- variations which can be corroborated by other means.

The Discovery: The Maps Don't Line Up

A handful of computationally minded linguists and linguistically minded computer scientists have been doing work on dialect geography using Twitter data, and I've found their work invaluable in developing this research. One of them, Gabriel Doyle (at UCSD), has demonstrated that dialect forms on Twitter correspond exceptionally well to the established gold standard of the ANAE. Like, uncannily, eerily well. He concluded, after some sophisticated statistical verification, that it's possible to glean geographic information about dialects from Twitter data.

His maps of double modals ("might could") and of the "needs washed" construction ("your car needs washed") line up perfectly with the maps produced by the ANAE and by the Harvard Dialect Survey (HDS).

My maps, however, did not line up.

Now, it has been known for a long time that including data from speakers of AAVE muddies things. In some ways, AAVE speakers do what other people in their general vicinity are doing, but in other ways they seem to do things differently. There's a large body of literature on this, but no national level description of regional variation in AAVE.

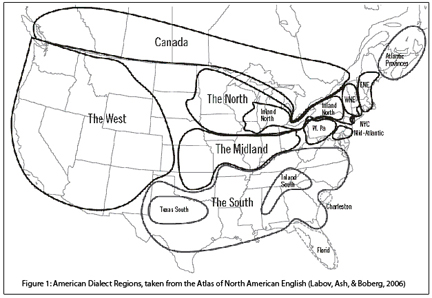

The standard maps of dialect regions in North America look like this:

Image from The ANAE, via the Texas English Project website: www.texasenglish.org

Notice the main feature is horizontal bands across the country, spreading from the East Coast. In some maps, the North, Midland, and South extend across the West, which is not given its own region. These regions follow patterns of westward expansion and settlement. In fact, maps of differences in building materials used in making cabins line up nicely with maps of dialect regions.

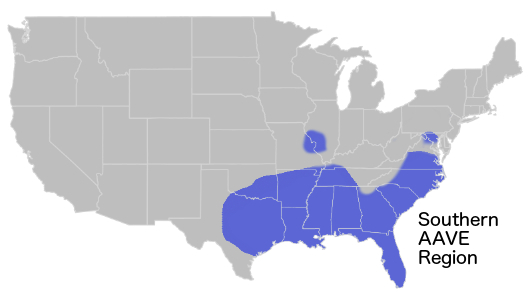

The thing is, AAVE does not share the same history as other North American dialects. Obviously, it is meaningless to discuss patterns of "settlement" when referring to black Americans, and while there is no consensus on the mechanics of how AAVE developed, it is understood to be largely an ethnolect, the product of a culture that developed in the last few hundred years shaped by (and despite) slavery, systemic racism, and extreme segregation.

In theory, then, the geographic distribution of AAVE should look different, and it should look roughly like the geographic distribution of Black Americans:

Image courtesy the Rural Assistance Center, from US Census 2010 data.

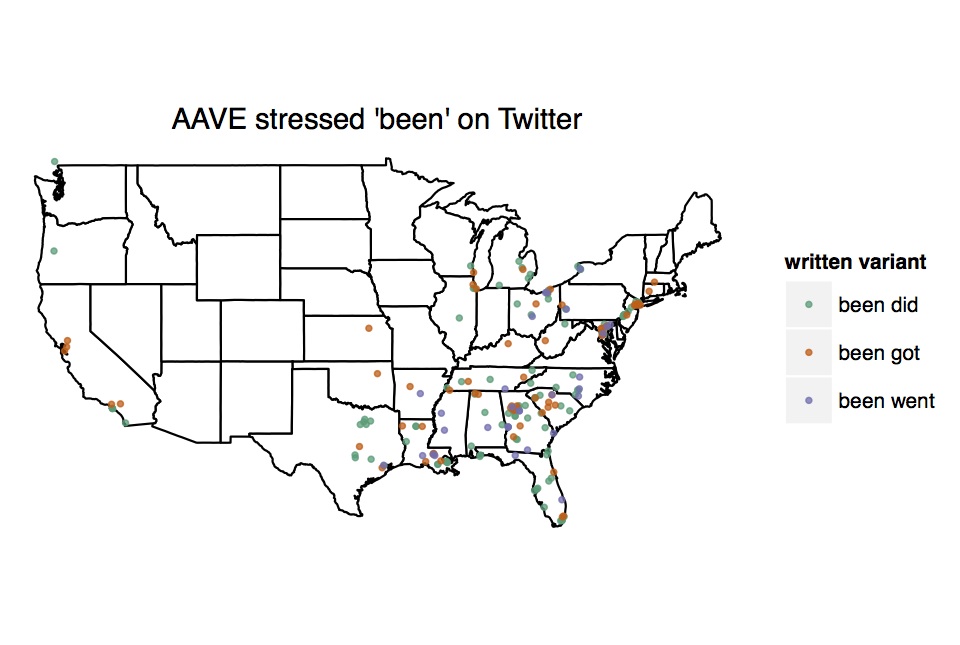

In some instances, this is what we see. For instance, when mapping AAVE-specific grammatical features like stressed been (which I discuss further here), the pattern lines up nicely with the population data:

initial exploratory plot of stressed been on Twitter

Note that tweets are concentrated in the South and the Northeast, and the areas with the highest black populations have the most tokens. Atlanta stands out particularly, but so do Oakland and LA, Chicago and Detroit. This pattern appears with other terms we'd expect to be non-regional, including nigga, tryna, and finna.

Similarly, enregistered lexical items (that is, local words famous for being local words) show up where we would expect them:

Philly's famously local word, "jawn," mapped on Twitter. Some of the unexpected points, on closer investigation, are people originally from Philadelphia. The two in Florida are someone referring to a friend named Jawn.

DC's newly famous "Jont." for more information, see Frances Sellers' fantastic article in the Washington Post, Is There a D.C. Dialect? It's a Topic Locals are Pretty Cised to Discuss, which discusses research by Georgetown's Minnie Annan.

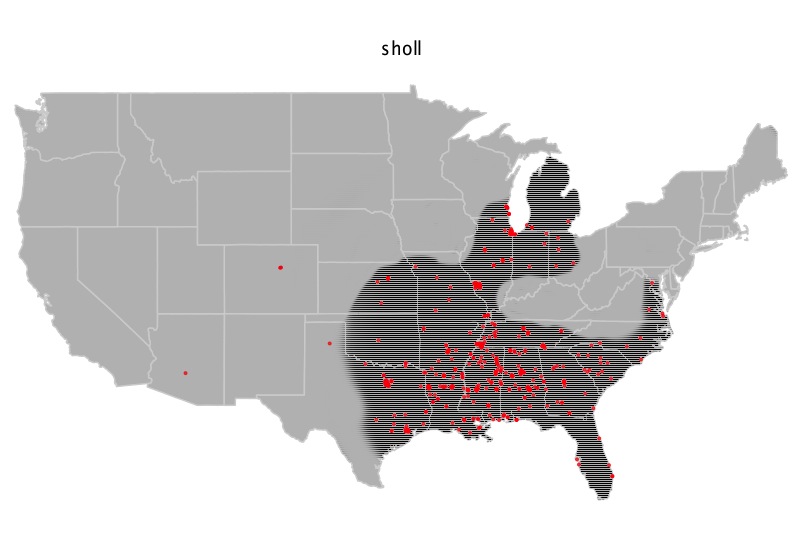

We see other, unexpected things, however. Things like this distribution of sholl for "sure":

This pattern sholl is peculiar.

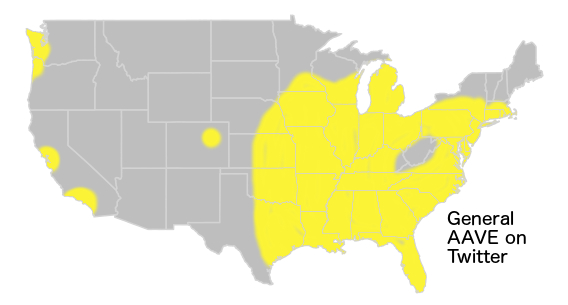

Once we map everything, we get a broad pattern, with some words (tryna, finna) completely non-regional, some (talmbout, sholl) in a band up the middle of the country, some (ioneem, nuffin) solely along the East Coast I-95 corridor, and some (yeen) only in the South:

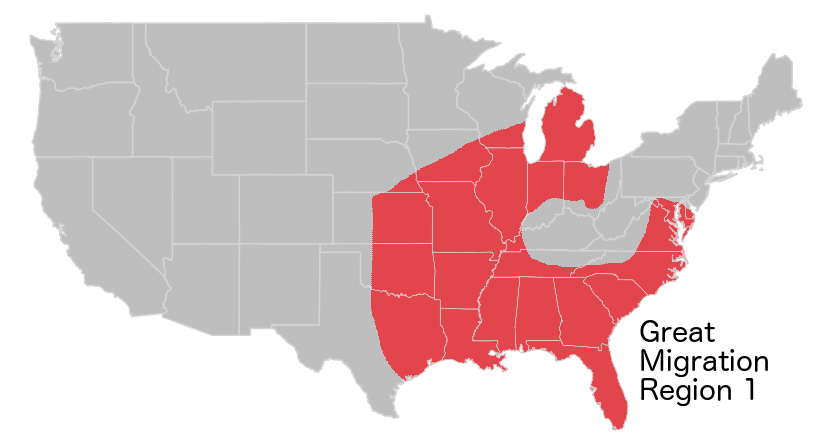

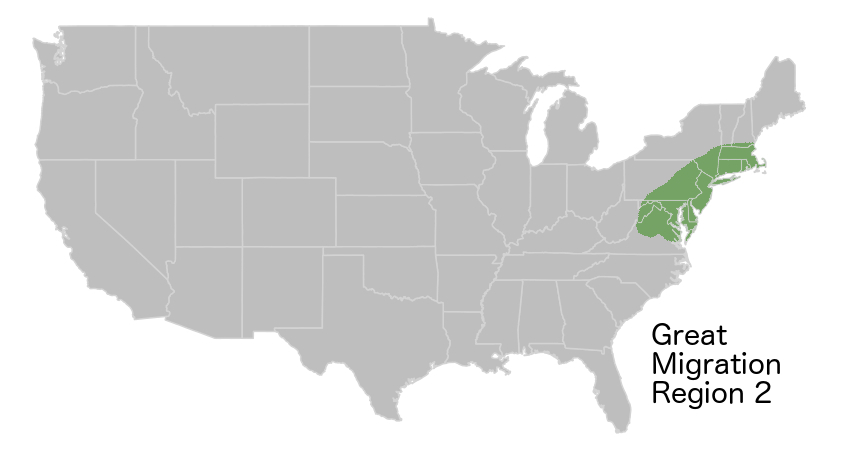

When I compared the maps of broad patterns of use in AAVE on Twitter to a map of the Second Great Migration from the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, the pattern, and its most likely historical cause, revealed themselves.

What we see on Twitter is exactly what a historical linguist would expect from migration and dispersal, followed in some regions by innovation. The South Central to Midwest corridor and the South share terms like the quotative talmbout and phonological features like the replacement of /r/ with /l/ in the word sure (e.g., "sholl is."). The South, and the South alone, has so called /ey/-raising, consistent with Southern American English, making you ain't into yeen, (whereas other parts of the country simplify it to yain). New York says "nuttin" and "suttin," but D.C. has nuffin, and Philly is split right down the middle by these competing forces:

"My bruva neva syced bout nuffin" - You a bama.

The above is just a small taste; I will be presenting quite a few more maps, and discussing the phonological data in much greater detail in my talk at the American Dialect Society annual meeting, this January. I'm also preparing a paper for publication. The key finding is that the pattern looks like what any historical linguist would expect after migration and innovation.

Why is this a big deal?

I'm extremely excited about this line of research, for a number of reasons:

- Not many linguists have been riding the big data wave. Instead, computer scientists with no training in linguistics are compiling huge data sets of, well, language, and they're doing their best to analyze it, and similarly linguists with no training in computer science are often ignoring the new tools at our disposal. In some instances, computer scientists are beating us to interesting discoveries. In others, they're getting flawed research past peer review because they're so unfamiliar with established concepts in linguistics that they think they've discovered "super dialects" when in reality they've stumbled upon register. We should all be collaborating, instead of reinventing the wheel.

This is the first attempt at defining dialect regions in AAVE on a national level, providing a baseline of research - a starting point for other researchers (and me, of course) to refine. For instance, there is a significant body of research that suggests "th-fronting" (that is, pronouncing words with a th like they have f/v, as in nuffin) is universal. While it may be possible to find everywhere (especially now that a Philly rapper has a hit song with the word "mouf" in the title!), it does not appear that way in these data. Moreover, in NYC, it's often interpreted as a marker that the speaker is not from here. Conversely, an informant I interviewed who had recently moved to Waldorf, MD, told me how he had to insist that his children do not say "nuffin," because he didn't want them "sounding like their peers in school," going on to say "everyone around here talks like that." In this way, participation or non-participation in these phonological patterns may be performatively indexing (non)local identity.

- This research relies on a new method of gathering data that can be complementary to traditional methods, and can help point toward new hypotheses, and new areas of research. For instance, some of the data suggest a syntactic change in progress (distinct from the one I'm presenting on at LSA 2015, in fact).

Ultimately, I'm excited because social media are new sources of data for linguists to take advantage of, and they're sources that are extremely rich and extremely large. Whereas Georg Wenker needed decades to send out 50,000 surveys and process the results, given the right question, we're on the cusp of being able to gather more data than that in just the better part of an afternoon.

I'm also excited because this research puts black folk back on the map, literally. It's time for a large scale, systematic description of regional patterns in AAVE like what we already have for other North American dialects, and this is a step toward it!