[content warning: language] [co-authored with Jessica Kalbfeld]

For the last four years I've been working on a large-scale project distinct from writing my dissertation that my family and friends know I refer to as my "shadow dissertation." It's a co-authored paper, with Jessica Kalbfeld (Sociology, NYU), Ryan Hancock (Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity, WWDLaw), and my advisor, Robin Clark (Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania), and we just received word that it has been accepted for publication in Language. Many of my other projects, including my work on the verb of quotation talkin' 'bout, on first person use of a nigga, and on the spoken reduction of even to "eem", among others, were all in service of this project.

Simply put: court reporters do not accurately transcribe the speech of people who speak African American English at the level of their industry standards. They are certified as 95% accurate, but when you evaluate sentence-by-sentence only 59.5% of the transcribed sentences are accurate, and when you evaluate word-by-word, they are 82.9% accurate. The transcriptions changed the who, what, when, or where 31% of the time. And 77% of the time, they couldn't accurately paraphrase what they had heard.

Let me be clear: I am not saying that all court reporters mistranscribe AAE. However, the situation is dire. For this project, we had access to 27 court transcriptionists who currently work in the Philadelphia courts -- fully a third of the official court reporter pool. All are required to be certified at 95% accuracy, however the certification is based primarily on the speech of lawyers and judges, and they are tested for speed, accuracy, and technical jargon.

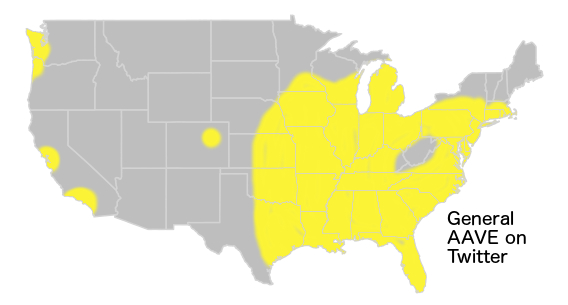

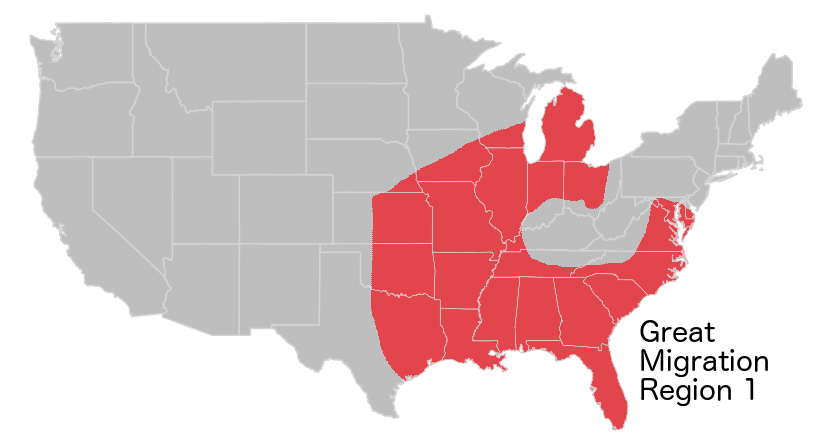

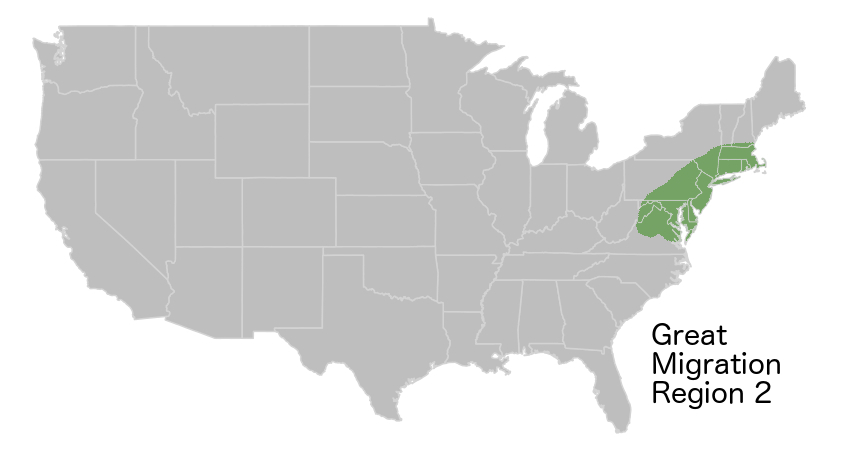

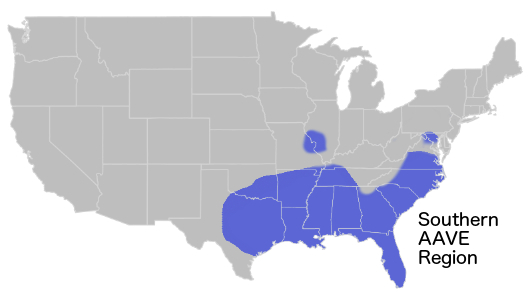

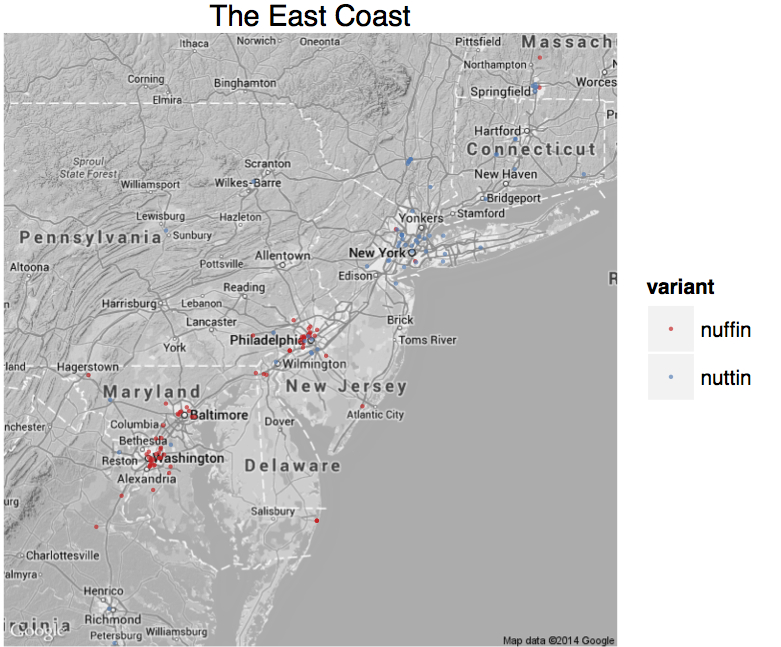

We recruited the help of 9 native speakers of African American English (if you're new to my blog, African American English is a rule-governed dialect as systematic and valid as any other), from West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, Harlem, and Jersey City (4 women and 5 men). Each of these speakers were recorded reading 83 different sentences, all of which were taken from actual speech (that is, we didn't just make up example sentences). These sentences each had specific features of AAE, 13 in total, as well as combinations of features. Examples of sentences included:

When you tryna go to the store?

what he did?

where my baby pacifier at?

she be talkin’ ‘bout “why your door always locked?”.

Did you go to the hospital?

He been don’t eat meat.

It be that way sometimes.

Don’t nobody never say nothing to them.

Features we tested for included:

null copula (deletion of conjugated is/are, as in he workin’ for “he is working”).

negative concord (also known as multiple negation or “double negatives”).

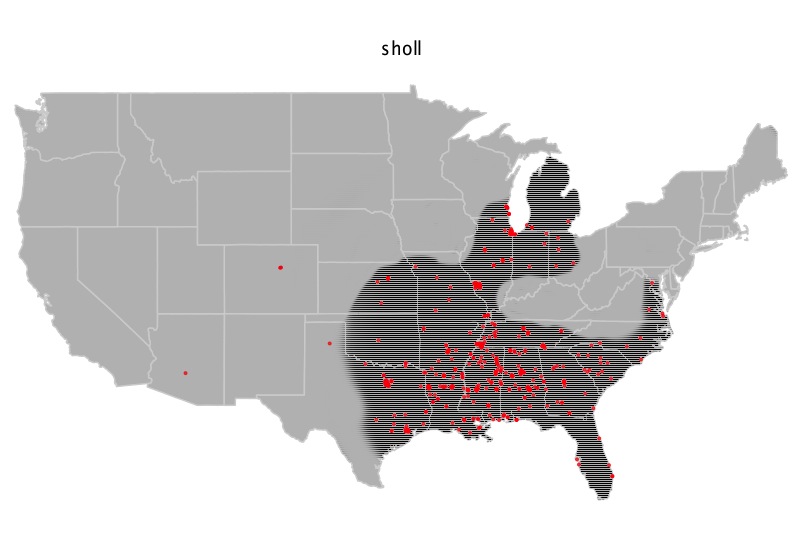

negative inversion (don’t nobody never say nothing to them meaning “nobody ever says anything to them).

deletion of posessive s (as in his baby mama for his baby’s mama).

habitual be (an invariant grammatical marker that indicates habitual action, as in he be workin’ for “he is usually working”).

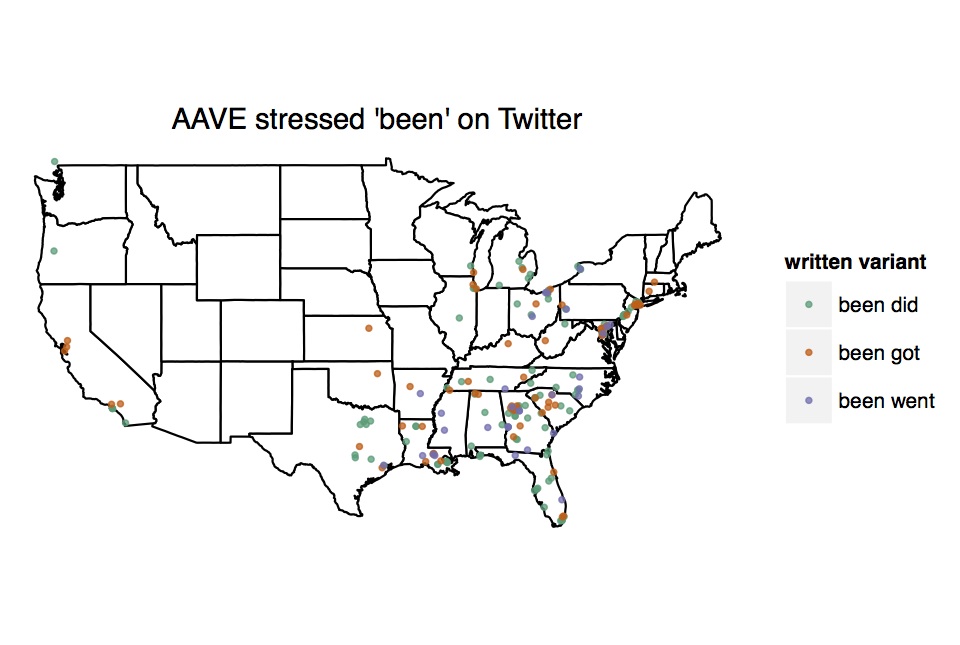

stressed been (this marks completion in the subjectively distant past, as in I been did my homework meaning “I completed my homework a long time ago”).

preterite had (this is the use of had where it does not indicate prior action in the past tense, but rather often indicates emotional focus in the narrative, as in what had happened was… for “what happened was…”).

question inversion in subordinate clauses (this is when questions in subordinate clauses invert the same way as in matrix clauses in standard English, as in I was wondering did you have trouble for “I was wondering whether you had trouble”).

first person use of a nigga (This is where a nigga does not mean any person, but rather indicates the speaker, as in a nigga hungry for “I am hungry”).

spoken reduction of negation (this is the reduction of ain’t even to something that sounds like “eem”, or the reduction of don’t to something that sounds like “ohn”).

quotative talkin’ ‘bout (this is the use of talkin’ ‘bout, often reduced to sounding like “TOM-out” to introduce direct or indirect quotation, as in he talkin’ ‘bout “who dat?” meaning “he asked ‘who’s that?’”).

modal tryna (this is the use of tryna to indicate intent or futurity, as in when you tryna go for “when do you intend to go?”).

perfect done (this is a perfect marker, indicating completion or thoroughness, as in he done left meaning “he left”).

be done (this is a construction that can mark a combination of habitual and completed actions, or can mark resultatives, as in I be done gone home when they be acting wild for “I’ve usually already gone home when they act wild”).

Expletive it (this is replacing standard English “there” with it, as in it’s a lot of people outside for “there are a lot of people outside”).

combinations of the above, as in she be talkin’ ‘bout “why your door always locked?” meaning “she often asks ‘why is your door always locked?’”

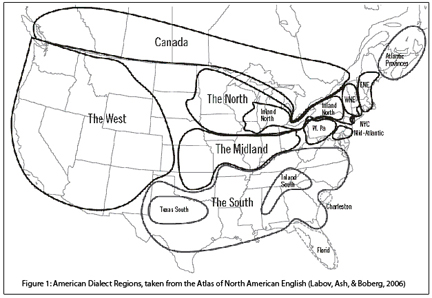

These are by no means all the patterns of syntax unique to AAE, but we thought they were a decent starting point. However, not only does AAE have different grammar than other varieties of English, but more often than not, African Americans have different accents from their white counterparts within the same city. Think about it: Kevin Hart's Philadelphia accent is not the same as Tina Fey's (it's also why Kenan Thompson's Philly accent is so weird in that sketch).

All of the court reporters we tested were given a 220Hz warning tone to tell them a sentence was coming, followed by the same sentence played twice, followed by 10 seconds of silence. We asked them to 1) transcribe what they heard (their official job) and 2) to paraphrase what they heard in "classroom English" as best as they could (not their job!). The audio was at 70-80 Decibels at 10 feet (that is, very loud). The sentences and voices were randomized so they heard a mix of male and female voices, and they didn't hear the same syntactic structures all at the same time. All of the court reporters expressed that what they heard was:

better quality audio than they're used to in court

consistent with the types of voices they hear in court (more specifically, they often volunteered "in criminal court").

spaced with more than enough time for them to perform the task (they often spent the last 5 seconds just waiting -- they write blisteringly fast).

What was the result? None of them performed at 95% accuracy, no matter how you choose to define accuracy, when confronted with everyday African American English spoken by local speakers from the same speech communities as the people they are likely to encounter on the job. If you choose to measure accuracy in terms of full sentences -- either the sentence is correct or it is not -- the average accuracy was 59.5% If you choose to measure accuracy in terms of words -- how many words were correct -- they were 82.9% accurate on average. Race, gender, education, and years on the job did not have a significant effect on performance, meaning that black court reporters did not significantly outperform white court reporters (we think this is likely because of the combination of neighborhood, language ideologies, and stance toward the speakers -- black court reporters distanced themselves from the speakers and often made a point of explaining they "don't speak like that."). Interestingly, the kinds of errors did seem to vary by race: there's weak evidence that black court reporters did better understanding the accents, but still struggled with accurately transcribing the grammar associated with more vernacular AAE speakers.

For all the court reporters, their performance was significantly worse when we asked them to paraphrase (although individual court reporters did better or worse with individual features. For example, one white court reporter nailed stressed been every time -- something we did not expect). Court reporters correctly paraphrased on average 33% of the sentences they heard. There was also not a strong link between their transcription and paraphrase accuracy -- in some cases they even transcribed all the words correctly, but paraphrased totally wrong. In a few instances, they paraphrased correctly, but their official transcription was wrong! The point here is that while the court reporters did poorly transcribing AAE, they did even worse understanding it -- which makes it no surprise they had difficulty transcribing.

In the linguistics paper, we go into excruciating detail cataloguing the precise ways accent and grammar led to error. However, the takeaway for the general public is that speakers of African American English are not guaranteed to be understood by the people transcribing them (and they're probably even less likely to be understood by some lawyers, judges, and juries), and not guaranteed that their words will be transcribed accurately. Some examples of sentences together with their transcription and paraphrase include (sentence in italics, transcription in braces <>, and paraphrase in quotes):

he don’t be in that neighborhood — <We going to be in this neighborhood> — “We are going to be in this neighborhood”

Mark sister friend been got married — <Wallets is the friend big> — (no paraphrase)

it’s a jam session you should go to — <this [HRA] jean [SHA] [TPHAO- EPB] to> — (no paraphrase)

He don’t eat meat — <He’s bindling me> — “He’s bindling me”

He a delivery man — <he’s Larry, man> — “He’s a leery man”

Why does this matter?

First and foremost, African Americans are constitutionally entitled to a fair trial, just like anyone else, and the expectation of comprehension is fundamental to that right. We picked the "best ears in the room" and found that they don't always understand or accurately transcribe African American English. And crucially, what the transcriptionist writes down becomes the official FACT of what was said. For 31% of the sentences they heard, the transcription errors changed the who, what, when, or where. Some were squeamish about writing the "n-word" and chose to replace it with other words, however those who did often failed to understand who it referred to (for instance, changing a nigga been got home 'I got home a long time ago" to <He got home>, or in one instance <Nigger Ben got home>, evidently on the assumption it was a nickname).

And it's not just important for when black folks are on the stand. Transcriptions of depositions, for instance, can be used in cross-examination. In fact, it was seeing Rachel Jeantel defending herself against claims she said something she hadn't that sparked the idea for this project. (And she really hadn't said it -- I've listened to the deposition tape independently, and two other linguists -- John Rickford and Sharese King -- came to the conclusion the transcription was wrong, and have published to that effect). Transcriptions are also used in appeals. In fact, one appeal was decided based on a judge's determination of whether "finna" is a word (it is) and whether "he finna shoot me" is admissible in court as an excited utterance. The judge claimed, wrongly, that it is impossible to determine the "tense" of that sentence because it does not have a conjugated form of "to be", claiming that it could have meant "he was finna shoot me." If you know AAE, you know that you can drop "to be" in the present but not in the past. That is, you can drop "is" but not "was". The sentence unambiguously means "he is about to shoot me," that is, in the immediate future.

This is excluding misunderstanding like with the recent "lawyer dog" incident in which a defendant said "I want a lawyer, dawg" and was denied legal counsel because there are no dogs who are lawyers.

All of this suggests a way that African Americans do not receive fair treatment from the judicial system; one that is generally overlooked. Most of us learn unscientific and erroneous language ideologies in school. We are explicitly taught that there is a correct way to speak and write, and that everything else is incorrect. Linguists, however, know this is not the case, and have been trying to tell the public for years (including William Labov’s “The Logic of Nonstandard English,” Geoffrey Pullum’s “African American English is Not Standard English with Mistakes,” the Linguistic Society of America statement on the “ebonics” controversy, and much of the research programs of professors like John Rickford, Sonja Lanehart, Lisa Green, Arthur Spears, John Baugh, and many, many others). The combination of these pervasive language attitudes and anti-black racism leads to linguistic discrimination against people who speak African American English — a valid, coherent, rule-governed dialect that has more complicated grammar than standard classroom English in some respects. Many of the court reporters assumed criminality on the part of the speakers, just from hearing how the speakers sounded — an assumption they shared in post-experiment conversations with us. Some thought we had obtained our recordings from criminal court. Many also expressed the sentiment that they wish the speakers spoke "better" English. That is, rather than recognizing that they did not comprehend a valid way of speaking, they assumed they were doing nothing wrong, and the gibberish in their transcriptions (see above examples) was because the speakers were somehow deficient.

Here, I think it is very important to point out two things: first, many people hold these negative beliefs about African American English. Second, the court reporters do not have specific training on part of the task they are required to do, and they all expressed a strong desire to improve, and frustration with the mismatch between their training and their task. That is, they were not unrepentant racist ideologues out to change the record to hurt black people — they were professionals, both white and black, who had training that didn't fully line up with their task and who held common beliefs many of us are actively taught in school.

What can we do about it?

There is the narrow problem we describe of court transcription inaccuracy, and there is the broader problem of public language attitudes and misunderstanding of African American English. For the first, I believe that training can help at least mitigate the problem. That's why I have worked with CulturePoint to put together a training suite for transcription professionals that addresses the basics of "nonstandard" dialects, and gives people the tools to decode accents and unexpected grammatical constructions. Anyone who has ever looked up lyrics on genius.com or put the subtitles on for a Netflix comedy special with a black comic knows that the transcription problem is widespread. For the second problem, bigger solutions are needed. Many colleges and universities have undergraduate classes that introduce African American English (in fact, I've been an invited speaker at AAE classes at Stanford, Georgetown, University of Texas San Antonio, and UMass Amherst), but many, even those with linguistics departments, do not (including my current institution!). Offering such classes, and making sure they count for undergraduate distribution requirements is an easy first step. Offering linguistics, especially sociolinguistics in high schools, as part of AP or IB course offerings could also go a long way toward alleviating linguistic prejudice, and to helping with cross dialect comprehension. Within the judicial system more specifically, court reporters should be encouraged to ask clarifying questions (currently, it's officially encouraged but de facto strongly discouraged). Lawyers representing AAE speaking clients should make sure that they can understand AAE and ask clarifying questions to prevent unchecked misunderstanding on the part of judges, juries, and yes, court reporters. Linguists and sociologists can, and should, continue public outreach so that the general public has an informed idea about what science tells us about language and discrimination.

This is a disturbing finding that has strong implications for racial equality and justice. And there's no evidence that the problem of cross-dialect miscomprehension is only limited to this domain (in fact, we have future studies planned already, in medical domains). This study represents a first step toward quantifying the problem and what the key triggers are. Unfortunately, the solutions are not all clear or easy to enact, but we can chip away at the problem through careful scientific investigation. On the heels of the 19th national observance of Martin Luther King Jr. Day (It has only been observed in all 50 states since 2000(!)), it seems appropriate to reaffirm that “No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

-----

©Taylor Jones 2019

Have a question or comment? Share your thoughts below!