Did Rich Lowry just say the N-word on Megyn Kelly's show? A Linguist weighs in.

Yesterday, discussing Haitian migrants in Springfield Ohio, and whether or to what extent they may or may not be abducting and eating (presumably white) Ohioans’ pets — because this is what the political discourse in the US is, and if we’re honest, has always been —Rich Lowry seems to have inadvertently used the n-word. Yes, that one. The one that rhymes with trigger, as in obvious trigger warning for content below.

Lowry is the editor in chief of the National Review, a conservative news and opinion magazine. He was in the process of explaining to Megyn Kelly that the facts of whether any actual Haitian migrants had engaged in culinarily-motivated cat abduction was immaterial, because what was important was the truth of the feeling the story captures. He made an explicit appeal to alternative facts.

He seems to say the n-word and then stammer and correct himself to “migrants.” His defenders argue he had misspoken, and said “mig-”, stammered, and then continued with migrant. Social media erupted, and people are passionately arguing about whether he said n*gger (ostensibly because that’s how he’s used to talking about Haitian migrants), or misspoke while saying “migrant" (and the whole thing is a disingenuous media witch hunt).

My goal today is to determine what he said, and whether either explanation for what people claim he said are plausible.

Unlike most writing about this controversy, I will be bringing to bear the linguistic tools of phonetic analysis to determine as best as possible what sounds were actually produced, and an understanding of psycholinguistics to assess the plausibility of various explanations of what may have been both said and intended.

Phonetic Evidence

All of the discussion I’ve seen of Rich Lowry’s ostensible slip of tongue has relied entirely on the person tweeting about it simply slowing down the audio.

Lowry appeared to be talking to Megyn Kelly via Zoom or a similar videoconferencing platform. He was wearing earbuds, and it does not appear that he had a microphone on the earbuds. He is, evidently, using the built in microphone on a laptop. He’s in a relatively large room, with glass windows. All of this negatively affects audio quality. Room size and glass lead to echoes. Built in laptop microphones do not sample with good quality, and the quality deteriorates the further away you sit. And Zoom (or similar platforms) may also compress or alter the audio. Twitter, where this was shared, further compresses both video and audio. However, the audio quality is still surprisingly good, despite the poorer video quality.

Regardless of the quality, simply slowing down the audio does not mean we will be able to accurately assess what sounds were made.

This is, in part, because we’re dealing with a “noisy” signal, and one of the things we rely in word recognition tasks is filling in missing information from context. With the context of a conservative commentator claiming it’s acceptable to insinuate Haitian immigrants could be engaging in pet-napping and then fricasseeing Fido because it feels true, a listener may be more likely to fill in a racial slur given an ambiguous auditory input. With the context of a left-wing witch hunt designed to disingenuously misrepresent a benign stutter, we may be more likely to fill in a false start to a normal word. There are tons of studies, going back to the 1990s, on hallucinated accents, and how our brains fill in missing information. In some studies, a ‘cough’ was superimposed over phonological segments, and participants heard different words depending on the linguistic context and their understanding of it. That is, we basically have a “blue dress” situation if we’re going by our ears alone.

For that reason, it’s important to use instrumental analysis rather than simply relying on our ears. To that end, I went to the Megyn Kelly show and trimmed the audio.

I analyzed the audio in Praat, and then attempted to clean it in Audacity before analyzing in Praat again. To do this, I amplified, analyzed a noise profile, removed noise, and amplified again. Nothing fancy.

Of particular interest to me was whether he said an /n/ or an /m/. Unfortunately, both are nasal segments, meaning they are produced by lowering your velum and allowing air to flow out your nose. This dampens sound, making the segments harder, but not impossible, to tell apart. And in fact, /n/ and /m/ differ by only one distinctive feature: the place where the airflow is constricted.

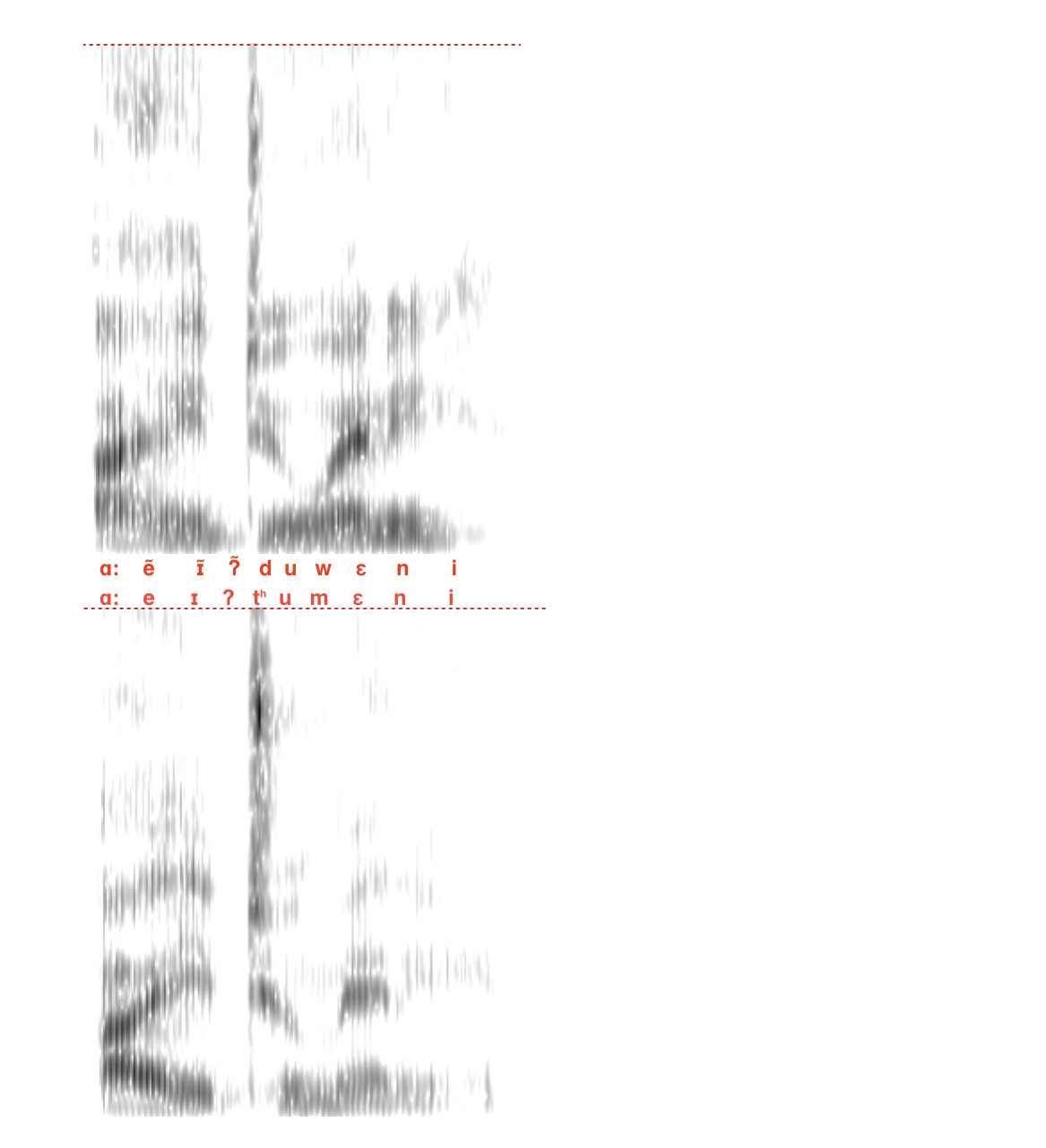

Nasals, like vowels, can be determined by the resonances that are amplified or dampened by the oral configuration, in particular the effect they have on these resonances (called “formants”) at the beginning of a subsequent vowel, or following a preceding vowel. If it’s an n, we expect a relatively stable second formant (F2), and if it’s an m, we expect a dip in both F1 and F2 (corresponding to the closure of the lips. Comparing the initial segment in Lowry’s mystery word to a later /m/ that we know was an /m/ in the intended word migrant, the formant transitions are clearly different.

Lowry’s initial segment is consistent with an /n/.

Not only that, but there is no change between the end of the word Haitian, and the beginning of the next word. It is entirely possible, but unlikely, that this is due to what is called progressive assimilation, in which the fact that /n/ and /m/ share a few distinctive features means they’re more likely to be assimilated in fast speech. Think gimme for “give me.” But also, regressive assimilation is more expected across word boundaries. Again, think gimme for “give me.”

Similarly, his second syllable is clearly not just a syllabic /ɹ/, but rather a vowel and /ɹ/: [əɹ].

The available evidence from instrumental measurement and spectrographic analysis is consistent with the phonetic string [nɪgər].

Just to be sure, I also used the overlap-add function in Praat to lengthen and slow the audio, and the result is inconsistent with multiple segments (as in [nm]).

Visual Evidence

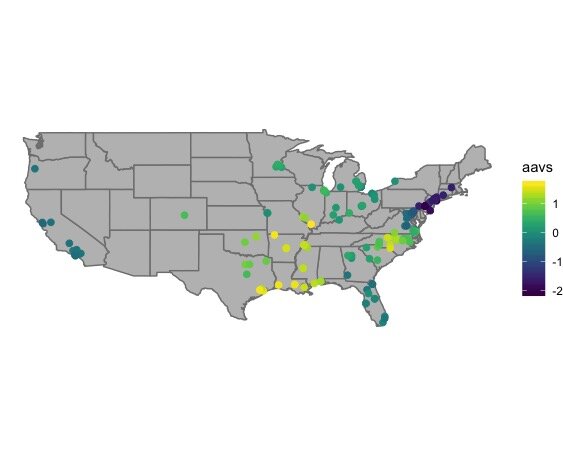

Obviously, m and n are produced with different articulatory configurations. Thankfully, they are distinguishable on video, since /m/ is produced by closing the lips fully (as is /p/ and /b/), and /n/ is not.

Comparing Lowry’s articulatory configuration in the word complain immediately prior to his mystery word to the onset of the word in question, it is clear that it is impossible for him to have been saying an /m/ (or /p/ or /b/).

Rich Lowry on the Megyn Kelly Show producing the /mp/ closure in the word “complain.”

Rich Lowry on the Megyn Kelly Show producing the initial nasal consonant in the mystery word, consistent with an /n/.

One could argue that the audio and video are insufficiently well aligned, and that it’s possible that I captured the final /n/ of Haitian, however I carefully tested the alignment on other words, paying particular attention to lip closure.

The visual evidence is consistent with an initial /n/.

Psycholinguistic considerations

The main defense that Lowry and his supporters have, is that it was simply a slip of the tongue, and Lowry was saying migrants.

In the most charitable reading of this defense — one which, bizarrely, nobody on his side has put forth — we might think that he had lexical interference from immigrant.

In what’s called a broad phonetic transcription, we might represent a careful, reading pronunciation of migrant as /ˈmɑ͡ɪ.gɹɛnt/, and a more casual pronunciation as /ˈmɑ͡ɪ.gɹənt/. The initial mark that looks like an apostrophe indicates that the first syllable is stressed. The a and i connected by a tie indicate that the first vowel is the glide “ay” as in “night.” The period represents a break between syllables. In the first, the “epsilon” e represents the e sound in a word like bed, and in teh second the upside down e represents schwa, the sort of ‘neutral’ vowel in an unstressed syllable.

The n-word, with what is colloquially referred to as a “hard r” is phonetically represented in broad transcription as /nɪ.gəɹ/ or /nɪ.gɹ/, with a syllabic /r/. That is, the r sound can be the syllable nucleus, a role usually taken by a vowel (but English allows for l, r, n, and m, under certain conditions). Note that the first representation of the n-word is consistent with the phonetic analysis from the spectrogram.

The word immigrant, is then /ˈɪmɪgrɛnt/.

Notice that a string of sounds in immigrant and one form of the n-word is exactly the same, namely, /ɪgɹ/ and the preceding segment is differentiated only by place. That is, m and n are very similar, being produced with voicing, and nasalization, but the closure for one is from the tongue behind the teeth, and the closure for another comes from the lips.

But is it plausible that this was a misfire? Perhaps he started to say immigrant and inadvertently continued with the final /n/ of Haitian, something like Haitianigrant. There are some challenges to the defense that he was starting to say immigrant.

First, the stress pattern is wrong. Immigrant is stressed on the first syllable, the im, part. Whereas that is entirely absent Lowry’s mystery word.

Second, in immigrant (and migrant), the r is not at the end of a syllable, but rather, is part of a syllable initial cluster: im.mi.grant.

It’s possible he thinks of that word as im.mig.rant. There are different ways people will syllabify a word when asked. However, the r is clearly not a syllable onset at all. So we’re left with “miggerant” and then a mispronunciation on top of that. Moreover, he stops himself before getting to the final syllable, almost as though there was no following syllable.

Third, words are generally processed linearly, meaning that if we were to see a misfire that affects initial segments, they’re likely to be spoonerisms: mixing up syllable onsets across word boundaries: runny babbit instead of bunny rabbit. It is highly unlikely that one would inadvertently drop the primary stressed syllable in a word. So, it is highly unlikely he was attempting to say immigrant, and misspoke.

But what about migrant? Here, we run into the problem that the vowel is different. At best, he said the non-word migger. It is, however, possible that he experienced lexical interference in attempting to say migrant from the morphological, phonological, and semantic overlap between immigrant and migrant.

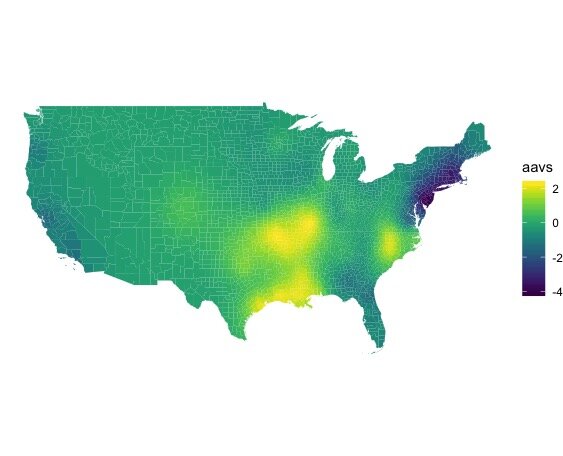

However, there’s another lexical interference claim that is possible: if he thinks of Haitian migrants as n*ggers, then that latter word will absolutely be primed for activation by both migrant and immigrant, especially in the immediate context of a word like Haitian.

Ultimately, either claim — that he was saying migrant or immigrant — have flimsy support at best.

Conclusions

It is my professional linguistic opinion that, based on the phonetic, physiological, and psycholinguistic data, it is most likely that Lowry inadvertently did indeed say the n-word.

In most contexts, I would caution against assuming anything other than an articulatory misfire, possibly from unfortunate lexical and phonological priming. However, given that he was in the process of arguing that knowingly making inflammatory false claims about Black immigrants engaging in morally abhorrent acts is not only politically expedient but actually in service of the greater public good, it seems at least plausible that this was simply a failure of his sociolinguistic monitor: the name given to a subset of executive function we engage in to not blurt things out that we might feel comfortable saying with our inner circle.

So at the end of the day, my professional opinion is:

Yes, Rich Lowry said the n-word.

It was most likely not accidentally producing an unfortunate string of sounds in an unflattering order but not intending to call Haitian migrants a slur. Rather, it’s likely he in fact, said the n-word as the n-word, and then sought to play it off as a slip of the tongue.