EDIT: This looks worse than I originally thought. The linguistic observations in this post are based on the video linked in the post (from early 2014), however, Rachel Doležal speaks differently in her recent interview with Melissa Harris-Perry. Looks like my new summer project is a more rigorous comparison.

By now, everyone I know has heard about Rachel Doležal, the former president of the Spokane, WA chapter of the NAACP: specifically, that she is a white woman who has been successfully posing as black for over a decade, and was recently outed by her white parents. Many of my friends have written thoughtful and interesting comments on the situation (e.g., Brianna Cox's take on it) and a few professors I know are discussing how to go about using it as a teaching moment (and what to take away from it).

While people have discussed power structures and privilege, passing and assimilation, whether "trans-racial" is really "a thing," and what Doležal's motivations could possibly have been, there are a few interrelated aspects of the increasingly ridiculous spectacle that have been overlooked, and which I find fascinating. Really, they're all facets of the same one observation:

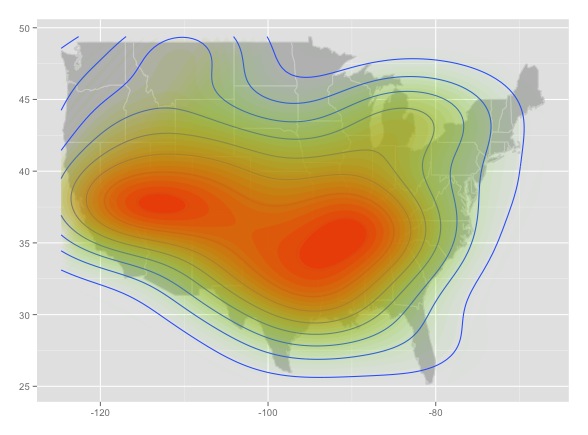

Rachel Doležal didn't bother to attempt ANY use of African American English. AT ALL.

Don't believe me? Here are videos of a 2014 interview with her.

This is incredible to me -- not in the sense of 'unbelievable' but in the sense that it's just astounding that she didn't use any AAE features and that she was right that she didn't need to in order to pass. For a decade.

First, I will explain what I mean when I say she didn't use any AAE features. Then I will discuss two interrelated possibilities: (1) she couldn't hear it well enough to even know she wasn't doing it, and (2) she made the decision that she didn't need to bother with speech after changing her appearance.

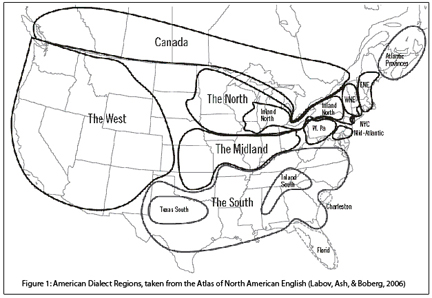

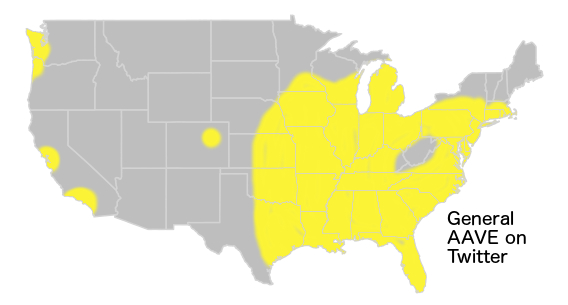

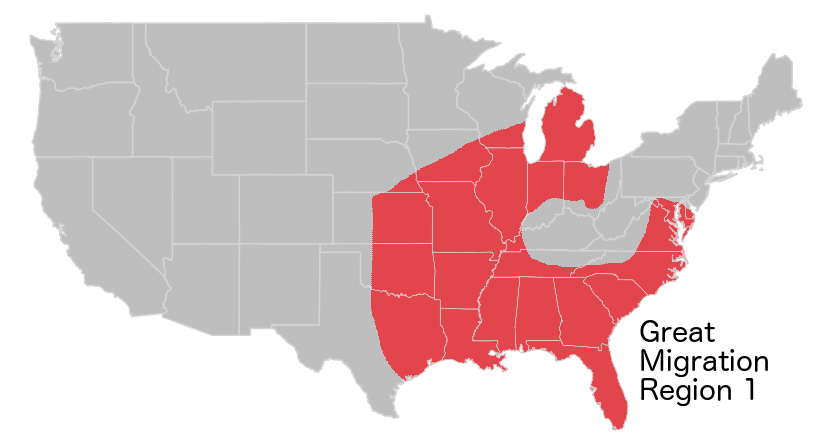

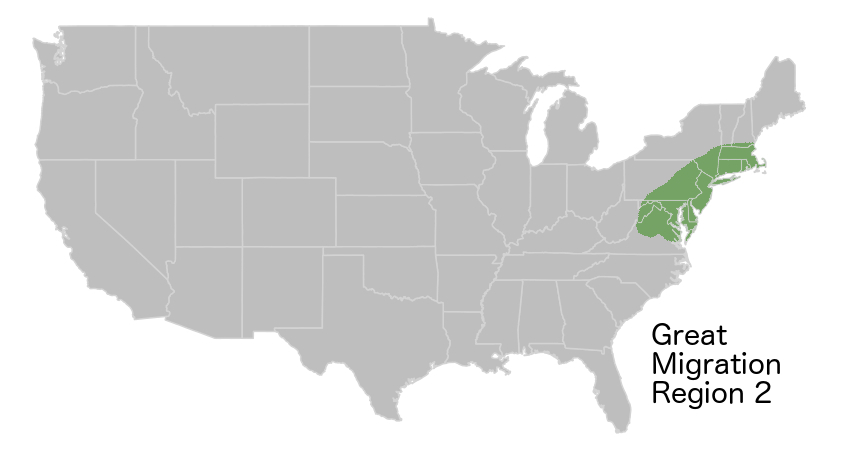

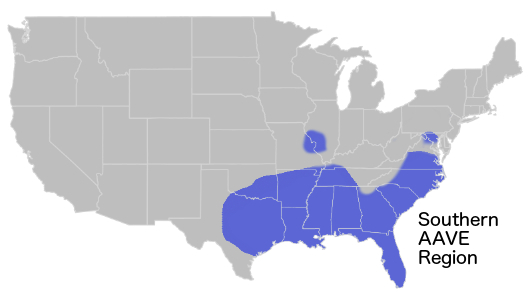

As a linguist, and as a white person who speaks AAE by virtue of my childhood speech communities, I am as aware as anyone could be that race and dialect are not intrinsically related. There are white people who speak AAE, there are black people who don't, there are people of both races who think they do but really don't (like this guy!), and ultimately though race is even more difficult to pin down than dialect both resist simple description (although dialects are easier to pin down). In the US, though, because of our history, there is an ethnolect spoken by many people who are raced (i.e, "perceived by most people") as black, and while it varies from speech community to speech community, it has overarching features that we can describe -- just like how we can talk about "French" despite the fact that what's spoken in Quebec is very different from what's spoken in Côte d'Ivoire.

What Doležal pulled off was the equivalent of successfully posing as a Parisian without having so much as a French accent, let alone speaking French. A black turtleneck, a beret, the occasional Galois cigarette, and voilà: you're French. Except in this example Doležal wouldn't have needed to say voilà.

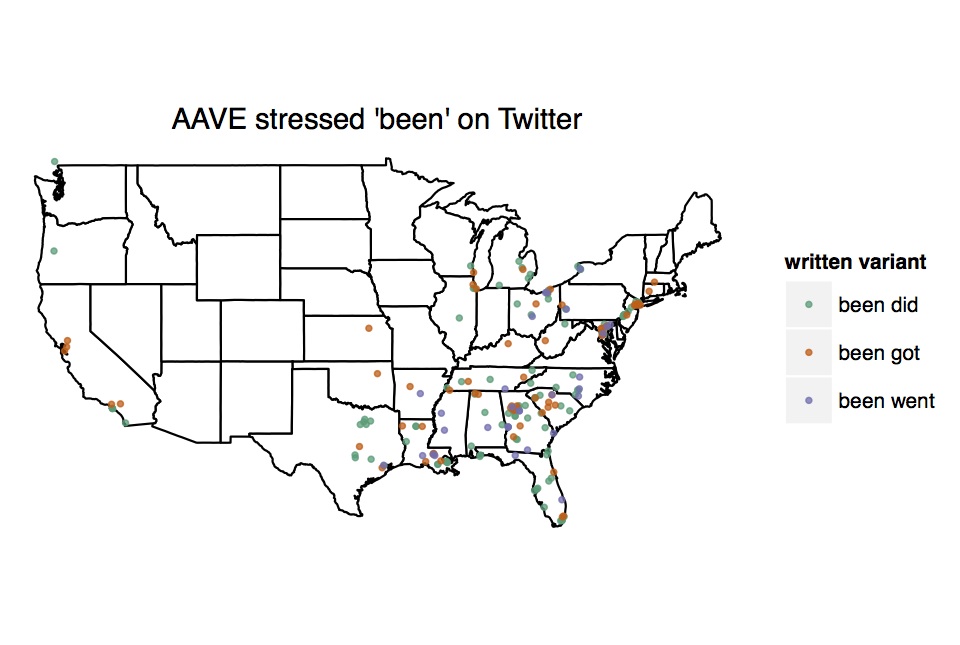

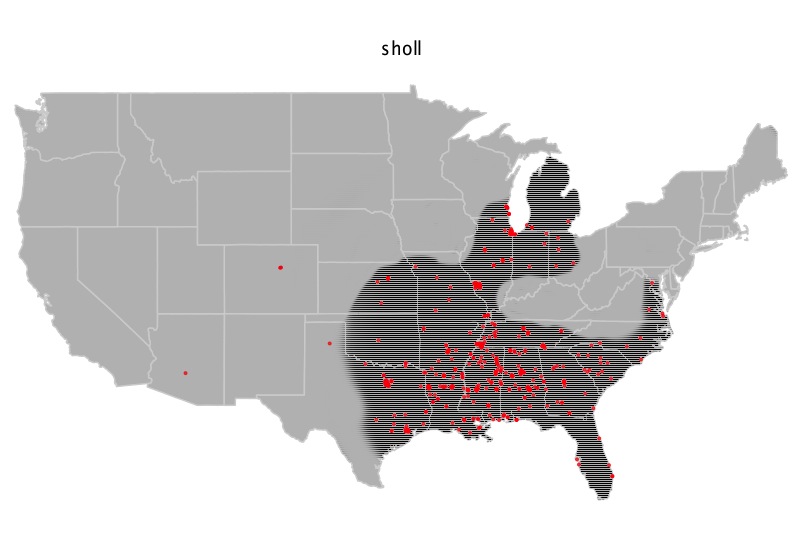

While no black American will necessarily speak with all the distinctive features of AAE, and some have none of the features of AAE, I'm flabbergasted by the fact that Doležal didn't bother with any. An excellent introduction to all the things she didn't do is Dr. John Rickford's article Phonological and Grammatical Features of African American Vernacular English. Listening to her speak, even accounting for the fact that it's a semi-formal interview and she's speaking in the capacity of Professor, it's still surprising how few features she exhibits. There are zero grammatical features: no habitual be, no stressed been, no preterite had, no AAE patterns of wh-operator and do-support inversion in main and relative clauses (relative to white North American Englishes), no done, no finna, no tryna, no typically AAE use of ain't, and so on and so forth. There's not even negative concord!

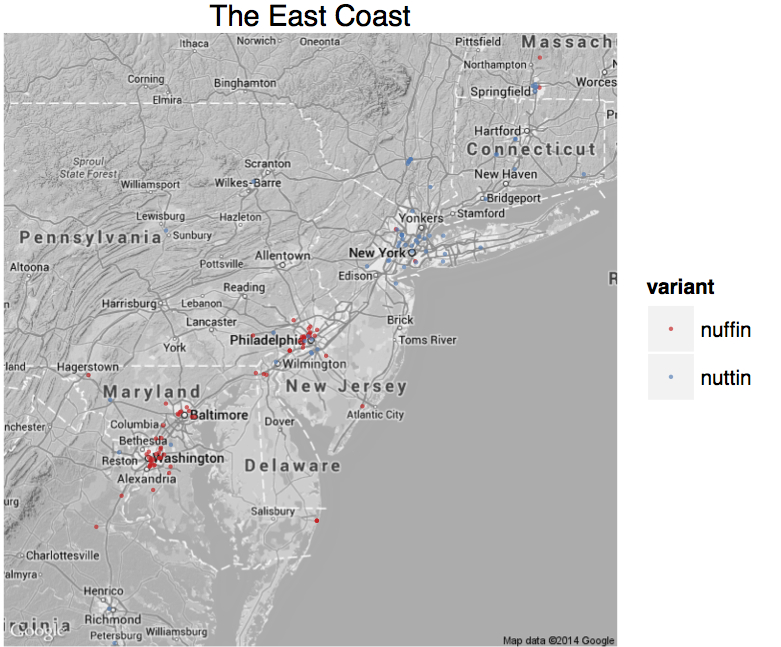

There are also very few to no phonological markers: she does not generally reduce consonant clusters (as in I was juss confuse for 'I was just confused'). She tends to fully release stops, even word finally, and she has no secondary glottalization on unvoiced stops. There's no word final devoicing of anything let alone deletion. Words ending with -ing don't get reduced to -in'.

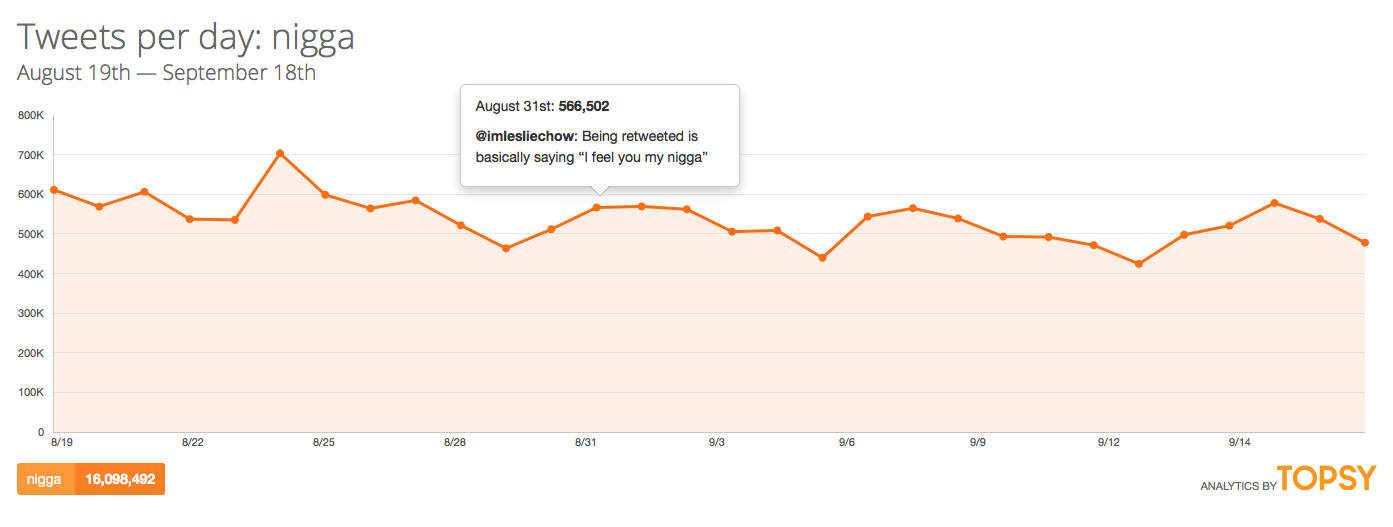

Finally, she doesn't use any AAE specific words or phrases. This is bizarre, especially given that she went to Howard. Even white non-speakers of AAE pick up words and phrases when they live in AAE speaking communities (it's called "accommodation"). I'm not expecting her, as a Howard grad, to use bama, lunchin', cised, press, or jont after leaving DC, but...like...give us something. Say bison after mentioning Howard (even though you sued them for 'reverse racism' when you identified as white, and lost). There's no stress shift, even in completely enregistered words, like police. There's literally nothing. It. Ain't. No. NOTHIN. What's perplexing about this is that such features can often serve as in-group signals that reinforce shared community, and so it would seem reasonable that she would employ some AAE features (1) to demonstrate she is actually 'down', and (2) to connect with her interviewer.

So the question here is: why no AAE?! I have two theories. The first is that she couldn't hear it. More precisely, she could hear something, but didn't know exactly what it was that made people speak differently, and if she tried to imitate it, found out she did so poorly. I did my undergrad in Canada, but while I knew there was something going on with Torontonians' accents, I couldn't imitate it successfully until I learned about Canadian Raising. I knew words: sore-E for 'sorry,' and when to use "eh", but saying "ooot" for "out" would have just oooted me as faking the accent. It may be that, having grown up in the Midwest and only encountering speakers of AAE after she went to Howard, at 18 years old, she just couldn't successfully acquire the phonology, and knew that if she tried it would sound like caricature. A friend of mine from Georgia can hear the New Yorkers around her saying /ɔ / in coffee and boss, but can't reliably produce it, and doesn't know which words to put it in. Others in a similar position try, but say "kwafie" and think they're succeeding. Maybe Doležal can hear AAE phonology, but isn't sure when to use it, and knows it sounds 'off' when she does.

However, this can't be the full story. She could have taken classes on African American English at Howard, and in an immersion environment for four years, she could have gotten good at it.

The other aspect to this situation is that she did the equivalent of a cost-benefits analysis and decided she didn't need to fake AAE to pass. One of my academic interests is Game Theory, and specifically Bayesian Signaling Games, which are surprisingly applicable here. In the simplest of this class of games, you have two possible types, and at least two possible signals. Agents try to infer the type of other agents by the signals those agents send. In pooling equilibria, there's no way of telling: agents of both types send the same signal and you can't glean anything from it. In separating equilibria, it's the opposite: you can completely categorize agents by the type of signal they send. Of course, the interesting class of games are those with semi-separating equilibria: this opens up the possibility of dishonesty.

In the Game Theory literature, there's also a distinction between cheap talk and costly signaling. The basic idea is that a signal that costs the sender something is potentially more trustworthy. If it costs me nothing to tell you something, it costs me nothing to lie, and if our interests are not aligned, you should be wary. Conversely, if our interests aren't aligned and I send a costly signal, that signal might tell you something useful, otherwise, why would I incur the cost of sending it?

If you were very white and chose to lie and pose as black, you would have to make decisions about what gives you the most bang for your buck, so to speak. It may be that Doležal made the evaluation that trying to use AAE features in her speech was already past the point of diminishing returns. In order to be immediately raced as black, you have to do something about appearance, although appearance alone isn't enough (the literature on passing and assimilation is relevant here). If you're going to pull off the deception, and if you're being rational about it, you want to do the minimum necessary to lie effectively, assuming going out of your way to lie incurs cost. She's trying to get the most value out of tricking people into believing she's black (being paid to teach classes, paid to be interviewed about black womens' experiences, presiding over a chapter of the NAACP, she's definitely getting value, even if we limit ourselves to financial terms only). She does so by doing the least: change her hair, think carefully about wardrobe, spray-tan but not too much. Monitoring your speech all day every day to imitate a dialect you did not acquire in the critical period? That's WAY harder.

In this respect, Doležal is reminiscent of various animals that successfully invade ecological niches, like bird species who replaces other birds' eggs with their own. She found the one niche where black women might have a slight advantage, and she did the minimum necessary to successfully signal that she was a black woman. And it worked for a decade. What's weird is that there are white professors of African American Studies, and white presidents of NAACP chapters, so it's not clear how much more advantage she got from posing as black, and she obviously incurred a cost (the enormous cost of being raced as black in America), although it may be that her values were such that she got some perverse benefit out of experiencing that cost (in a discussion of Bayesian Games in his excellent textbook on Game Theory, Steven Tadelis refers to a type that derives perverse pleasure from what should be a losing strategy as the "crazy" type.).

It seems that the obvious cost of being black in America was strong enough that, in combination with the minimum necessary changes to plausibly looks some kind of black, everyone just went with it, since it is a priori bat-shit crazy to pose as a disenfranchised type rather than posing as the type with the significantly higher expected value (in everything from educational outcomes, to interview call-backs and job prospects, to heart disease and life expectancy, to interactions with the police. EDIT: Here's a clue to the expected value). So, given that it seems crazy to pose as black, everyone just went with it -- for a decade, people made the Bayesian calculation "what is the likelihood she's not black and just faking it given (1) her appearance and overall bearing, and (2) the relative costs and benefits of being black versus being white in America?"...and came to the rational, but wrong, conclusion that she was being truthful.

If the above is right, it has an upsetting implication for the trans-racial camp. She claims she feels black, and that she's really black, whether her ancestry is or is not. If she has such an affinity for blackness, why then do the bare minimum to pass? I'm not black, but I'm a white ally with positive feelings toward a number of black cultures, and I use AAE not just because I am natively able to speak it, but because I like it and I respect it. What is most disturbing about what's coming to light about Doležal is that she seems to have a love-hate relationship with the idea of blackness that tends surprisingly toward hate, and tends toward caricature where it's love. She sued Howard University for being pro-black at her (white) expense (and lost), and then did the minimum to take on the mantle of blackness to benefit in precisely the ways she claimed actual black people were benefiting at her expense, and she did so in a places where there are the fewest actual black people around to compare against or to call her bluff. And, now, Black Twitter has called her bluff precisely in this arena, with #AskRachel, giving multiple choice questions 'any' black person should know the answer to, where the answers are [SPOILERS] things like "they smell like outside," or the word for "remote control" is C) Moken Troll.

I'm not sure what more to say about this other than: I can'eem deal right now.

-----

©Taylor Jones 2015

Have a question or comment? Share your thoughts below!